As we move one year closer towards ambitious Net Zero targets, the UK Government faces an imminent decision on whether or not to implement embodied carbon regulation. Hesitation around this decision comes at a time when embodied carbon (emissions arising over a buildings lifecycle) threatens to overtake operational energy use as the sector’s primary carbon source, leaving the UK’s construction industry no longer wondering whether embodied carbon regulation is necessary, but how long the UK can afford to delay its assessment. This article discusses the differences between operational and embodied carbon, explores the barriers, benefits and support of mandatory reporting and why this matters within the UK construction industry.

Embodied carbon is defined as the total carbon emissions produced throughout a building’s entire lifecycle, excluding its operational energy use. It contributes to roughly 20% of UK built environment emissions currently, but this is ever rising. Due to buildings increasing in energy-efficiency and grid decarbonisation, operational carbon is falling, meaning that embodied carbon will account for over half of built environment sector’s emissions by 2035.

Operational Carbon vs Embodied Carbon

As embodied carbon is released upfront, it cannot be reduced post-build unlike operational carbon which you can improve over time through retrofits or switching renewable energy. Consequently, regulatory targets, and standardisation methods of measurement are likely to help quantify emissions, develop science-based targets and hold building developers accountable. However, embodied carbon remains largely unregulated in the UK, resulting in a fall of only 4% between 2018 and 2022, 13% off the reduction target. Compared to operational carbon, these fell successfully in line with stated targets supported by extensive regulation.

| Operational Carbon | Embodied Carbon | |

| Definition | Carbon emissions arising from the energy used to operate a building during its lifetime | Carbon emissions from the materials and construction processes used throughout a building’s lifecycle |

| Practical Example | Electricity powering office lighting and IT equipment Air conditioning cooling a commercial building | Concrete and steel manufacturing and transport Demolition waste processing |

| Mitigation Strategies | Improved insulation and airtightness Renewable energy generation Energy-efficient appliances | Using less material and low carbon or recycled alternatives Local material sourcing Building reuse and retrofit |

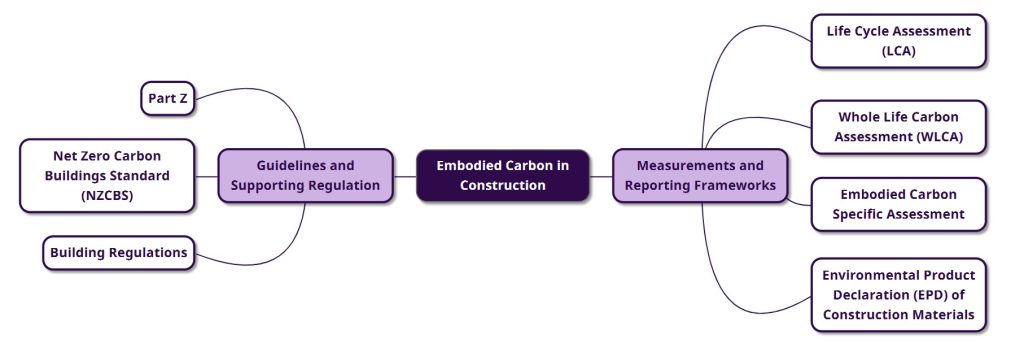

| Supporting UK Regulation | Extensively documented: Building Regulations Part L (Conservation of Fuel and Power) Future Homes Standard 2025 Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) requirements | Currently unregulated, industry-led initiatives include: Part Z Building Regulations RICS Whole Life Carbon Assessment and the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard |

Part Z – Industry-led Change

Part Z is an industry-proposed amendment to UK Building Regulation 2010, written to require developers to assess and limit the whole-life carbon emissions of new construction projects. It suggests that major projects (of over 1,000m2 or 10 homes) would first be required to report their carbon emissions, followed by the introduction of mandatory limits on upfront embodied carbon emissions. The goal is to regulate the carbon footprint of the construction process, instead of solely documenting the operational carbon of the finished building.

Barriers to Regulation

This approach is backed by industry leaders such as the Institution of Structural Engineers (IStructE) and UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) and supported by a further 105 company pledges. However, almost 5 years on from its original proposal, it is still yet to become law. This has led to pressing questions arising about the UK Government’s priorities regarding the UK construction industry, and its responsibility within net zero targets.

In an interview with Will Arnold, of IStructE and an author of Part Z, The Building Cost Information Service suggests that government hesitation comes from concerns about meeting housebuilding targets. This uncertainty stems from the effects that implementing this policy could have on increasing the difficulty of building much needed homes. However, Arnold, explains that the regulation could still be applied to larger developments, to avoid building unnecessary barriers for smaller projects. Increasing project costs by undertaking an embodied carbon assessment is also a key worry, but this fails to recognise the monetary positives in increasing material efficiency, reuse and transport distances, all arising from reducing embodied carbon.

Looking further afield, the European Union has taken a progressive approach, mandating Member States to report embodied carbon by 2028. The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) requires that all new buildings must calculate and report whole-life carbon emissions, plus member states must establish maximum thresholds for embodied carbon, which will gradually decrease after 2030. Prior to the implementation of the EPBD, several EU countries already had national regulation regarding embodied carbon, showing a clear recognition and commitment to eliminating this major contributor of emissions.

The Benefits of Lowering Embodied Carbon

Despite Part Z not becoming regulation, industry continues reducing embodied carbon, and the UK Green Building Council published the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard in 2024. This document calls for the assessment of both embodied and operational carbon using a whole life carbon approach. Similarly, developers can elect to assess their embodied carbon emissions on a project-by-project basis. This approach demonstrates environmental leadership for those who choose it, whilst meeting the rising demand from both industry stakeholders and the public.

- The Forge, London, United Kingdom, 2023

The Forge, a collaboration between Landsec, Bryden Wood and Easi Space is a development of two nine-storey commercial office buildings in London. It is the world’s first major commercial building constructed using a platforms approach to Design for Manufacture and Assembly (P-DfMA). It also used a minimised basement size, decarbonised MEP services (using heat pumps instead of gas) and opted for low carbon material specifications resulting in a 39% reduction in upfront embodied carbon. Further calculations tracked changes from the baseline through to completion in 2023 and found that embodied carbon accounts for roughly two-thirds of whole life carbon over 60 years, with operational carbon making up the remaining third.

Timeline to Implementation

Embodied carbon is soon to dominate built environment emissions, yet it remains largely unregulated in the UK. Thoughtful design and material choices reduce emissions, but progress depends on voluntary action and industry leadership without regulatory backing. As operational carbon continues to fall and embodied carbon’s share grows, the case for regulation becomes harder to ignore. Seemingly, one question remains; how long will the UK wait to implement embodied carbon regulation?

Supporting Your Embodied Carbon Reporting

Decerna helps UK construction organisations navigate new compliance requirements through our comprehensive consultancy and development services. Our extensive experience in Life Cycle Assessment makes us one of the longest-established UK consultancies in this field, offering ISO 14040/44 LCAs and EPDs, along with WLCA and Embodied Carbon Assessments. Our capabilities extend to providing Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism support, comprehensive carbon reporting covering all Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, and developing bespoke carbon reduction and Net-Zero plans.

Written by Helen Brown